“‘The Biggest Business in the World’: The Nestlé Boycott and the Global Development of Infants, Nations, and Economies”

"The old hierarchies of protection and dependency no longer exist, there are only free contracts, freely terminated. The marketplace, which had long ago expanded to included relations of production, has now expanded to include all relationships."

– Barbara Ehrenreich

This is a book about the incorporation of humanity and the privatization of life itself. In the 1970s and 1980s, concerned observers saw two acts of violence unleashed upon poor women in less developed countries, and, simultaneously, every individual on earth. At the most personal level, global infant formula companies forced their manufactured commodities into the most intimate site of human relations: the nursing infant at her mother’s breast. At the other extreme, nuclear warheads imperiled the world’s population. Activists around the world struggled against these developments, and the intersection of the two issues revealed deep fears about society’s priorities, apocalyptic visions of the future, and the survival of the species.

Cartoonist Joseph Conrad in INFACT News. Tamiment Library, Robert F. Wagner Labor Archive

My research explores the context of the above cartoon in order to analyze intensifying millennial fears during the 1970s and 1980s, and the politics that resulted from those anxieties. The cartoon, published in an activist newspaper, reflected concerns about the increasing power of multinational corporations, and the destruction of all sorts of environments – ecosystems, communities, and even infant bodies corrupted by the profit motive. During the rise of “scientific motherhood,” and especially the medicalization of birth, infants were often taken from their mothers and fed infant formula instead of breastmilk. Into that space between mother and child arrived products scientifically formulated and processed by food engineers. For some observers, it seemed that human survival itself had become commoditized.

We live on a privatized planet, amidst intensifying economic and social inequity. The contested spread of global capitalism has often assumed ownership of everything, from water to our bodies. Food companies discipline people to grow and develop according to market prerogatives. Pharmaceutical firms teach us how to heal, and remain sane, using their expert knowledge and scientific advancements. Health professionals and international policymakers have largely acquiesced to the neoliberal agenda. This historical evolution has occurred at the moment the human species has become a geological agent in its own right, ushering in an epoch some scholars call the Anthropocene. Researchers have primarily addressed these developments through social science, using ahistorical models like “species,” “capitalism” and “the economy” as static units of analysis. Meanwhile, seven billion people live within one distinctive ecosystem, and life on this planet, whether owned or shared, seems to be imperiled. Corporate culpability within a broad human rights framework sets the stage for the most important social, political and economic struggles of our time.

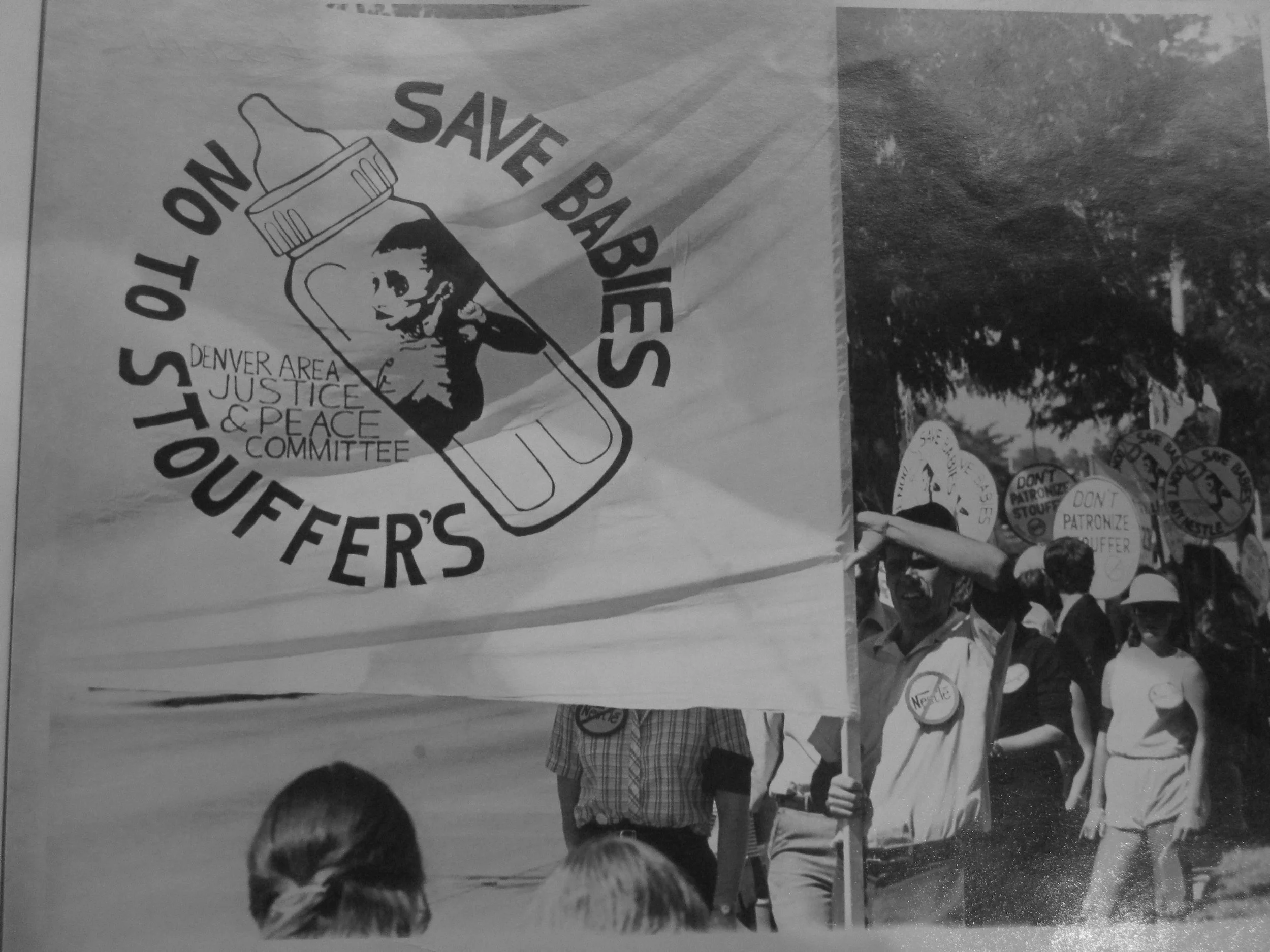

“The Biggest Business in the World’: The Nestlé Boycott and the Global Development of Infants, Nations, and Economies,” is a study of a boycott in the 1970s and 80s against Nestlé SA, the largest food company on the planet. Activists accused the Swiss company of killing babies in developing countries with its infant formula products. Nestlé countered that it and the formula industry actually saved babies, contributed to local development, and solved many of the world’s economic and health problems. When critics gathered instances of corporate advertising across the so-called Third World, they saw a deleterious and racist imperialism at work, if not a new form of economic colonialism. Additionally, they critiqued corporate and institutional assumptions about women’s bodies, breastfeeding decisions, and reproductive choice. Women and children, therefore, demonstrated their life choices and political struggles within a spectrum from women’s health to world health. Individual aspirations for an improved quality of life, however, increasingly relied on corporate answers to local problems, supplied for a price.

By the time the Nestlé boycott was launched in the late 1970s, Nestlé and other baby formula producers had more than a century of experience convincing women to turn away from natural breastfeeding to the bottle. Birth and childrearing also became medical problems to be decided in hospitals by health professionals rather than by ordinary women. The politics of breastfeeding thus took shape within the overlapping domains of medical professionalization, scientific management, and consumer capitalism. Intense personal, local and ultimately global struggles rested on the political site of a woman's body and her feeding child. By studying these transnational political contests, I illustrate the shift from political, economic and social possibilities in the 1970s, to neoliberal consolidation after the Reagan Revolution and the latest stages of globalization. Even within the World Health Organization, the transformation from the postcolonial emphasis on economic justice and human rights to privatized global health policy was shocking. Denaturalizing industry’s power and its prerogatives remains a critical scholarly project.

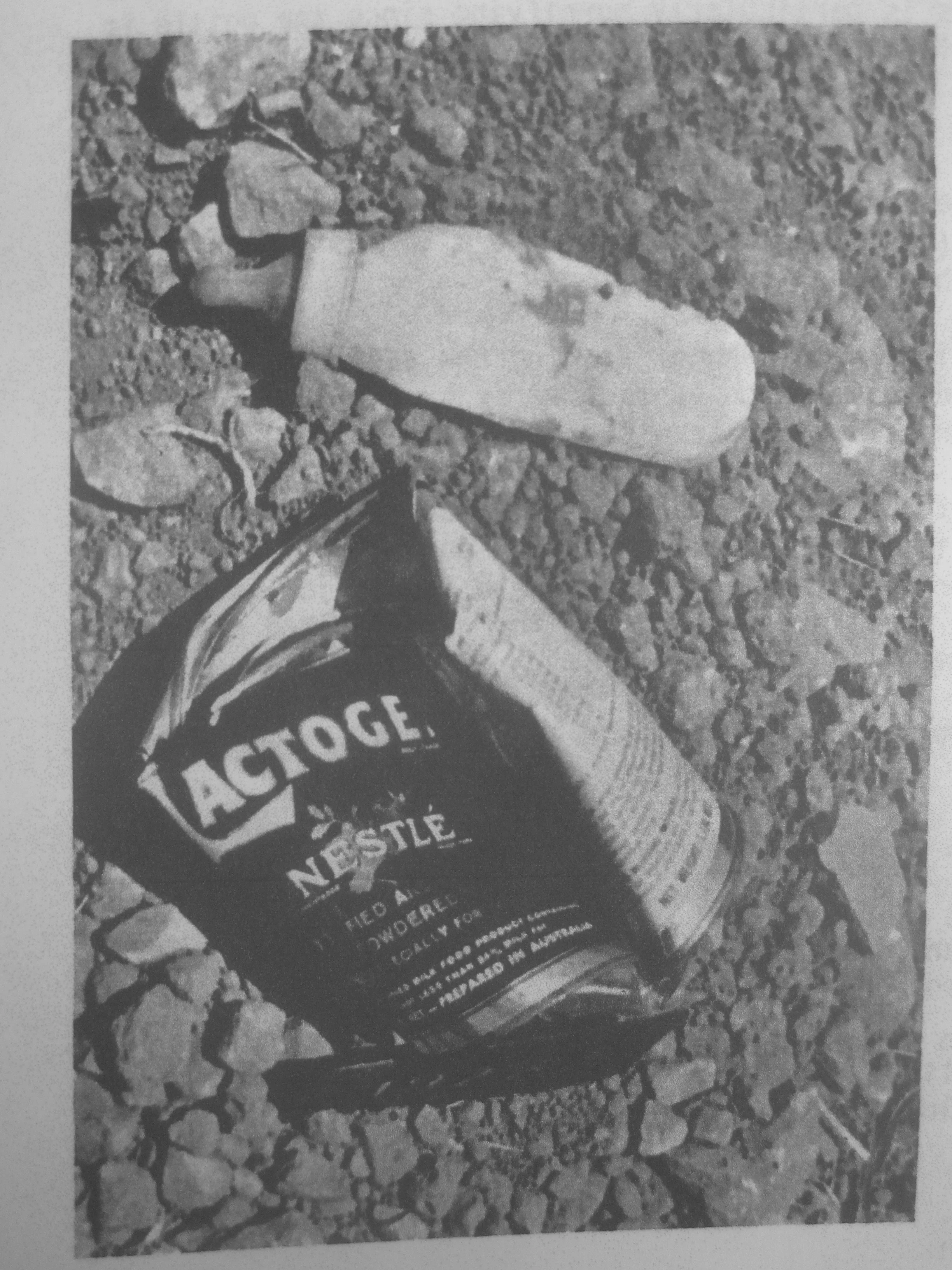

The landmark global struggles of the twentieth century—capitalism vs. communism, imperialism vs. decolonization, traditionalism vs. modernity, the West vs. the Global South, scarcity vs. abundance, the so-called welfare state vs. neoliberalism—converged in the competing images of two babies in the 1970s. In one, there is an emaciated African infant, ribs prominent, large skull too heavy for its body, severely malnourished and near death, lying on her back next to her brother's grave. On the grave, sticking out of piled dirt, rested a baby bottle, there because of its supposed magical powers that would accompany the dead infant into the afterlife. In the other image, a healthy white baby with fat, rosy cheeks, sits next to a canister of infant formula, smiling and ready to grow and develop according to proper growth charts. Anti-formula activists distributed the first image in order to gain support for a global boycott of infant formula sold in the Global South by multinational corporations. Food and pharmaceutical companies offered the second image as an advertisement for their scientifically manufactured baby foods. Throughout my work, I argue that we threaten to “incorporate” all of Humanity, with borderless power structures auguring greater injustice, implicating ourselves in a global domestication from individual and village to the species.

The politics of baby food and breastmilk existed at all because corporations, states, international organizations and women themselves fought for the terrain of what George Gilder termed "the future of capitalism." And here, inexorably, capitalism entwined with feeding regimes, survival strategies and the convergence of history and biology. In the 1970s, women across the world felt the invisible hand all over their bodies, and they demanded more of a say about how they fed their babies, constructed their families, and managed their individual survival strategies. Corporations, through marketing and various distribution techniques, tried to influence their decisions. Market openness, whether continental or global, has been a central story in humanity's political and social organizations over the last five hundred years. But where has this expansion left us, as a body? I hope this book contributes to an answer, showing that the domestication of humanity as an imagined global species has harnessed the imperial destructiveness of a rampant bio-organism on a specific, embodied biosphere. Capitalism or no, people in the late 1960s, the 1970s and the 1980s developed both radical and reformist answers to that destructiveness, and they began by saving babies and trying to regulate multinational corporations in an effort to save the world.

This work also wrestles with a number of seemingly self-evident keywords. “Development,” “growth,” and “hunger” were not objective descriptors of material conditions, but contested terrain for various historical actors to make claims. For example, nutrition expert Alan Berg understood that improved nutrition of babies and children also led to improved economic growth, and citizens’ contributions to the national economy, to GDP. Certainly, that framing is how he pitched funding projects to the World Bank. Still, many people, on various sides of the political debates, viewed underdevelopment as pathology. Growth and health, then, seemed to exist as some sort of halcyon, with growth a unifying, universal language; many others saw growth as a disease, a sickness like cancer. And yet, poor people with poor diets fit into economists' equations with the ultimate aim of improving growth and productivity. The proliferation of quantitative metrics like GNP is something that we must interrogate, recognizing the development and deployment of such metrics to be argumentative not objective.

The success of corporate entities in the commodification of nature, especially food supplies, created a system in which human survival itself was a matter of market forces more than biology. When milk for babies became a consumer good, it signified the capacity of global capitalism to commodify the most elemental necessities of life. Formula companies made money on that early separation of baby from mother. Profits soared when bottles proliferated. Through this process, planned and materialized, companies and health professionals removed the baby from the mother, and the mother's alienation from the product of her own labors, that is, her own child. Many activists saw companies as producing babies for a system predicated on private property and the accumulation of wealth. Survival had become privatized. The infant formula industry universally believed that they helped babies grow and develop, provided proper nutrition, and solved scarcity through open markets. Bristol-Myers testified that they were in the business of life itself.

The problems of scarcity and abundance vis-à-vis environment became a pressing international issue that exploded in the 1970s. Increasingly, many studies explore what some have called "species solidarity," a global consciousness, or even the "globalization of the world picture," according to historian Benjamin Lazier. Indeed, activists, politicians and capitalists visualized the entire globe as a place for struggles over influence that required expert attention in order save the world from ecological destruction, famine, and intense poverty. Conceptions of the earth, like the changing conception of earth from an earlier era based on images of our planet from space, explored in Donald Worster's "Vulnerable Earth" essay, contribute to an intellectual history of earth-centered thinking or global consciousness. Marxist geographer David Harvey studied the "geopolitics of capitalism" and outlined the structural problems of capitalism to human well-being. For him and many others, the stakes of non-sustainability were ecological destruction and threats to the existence of human life on this planet. I situate my work within this conversation by analyzing contemporaneous struggles over growth and ecological limits and the discourses that surrounded them, but problematize the conversation by claiming that “growth,” as rhetoric and practical strategy, was the dominant view that followed infant, corporations and entire nations.