An exploration of growth, development and the total privatization of the species.

INTRODUCTION

The Biggest Business in the World

"The old hierarchies of protection and dependency no longer exist, there are only free contracts, freely terminated. The marketplace, which had long ago expanded to included relations of production, has now expanded to include all relationships."

"A nation grows out of its children."

"Breast milk is a universal food."

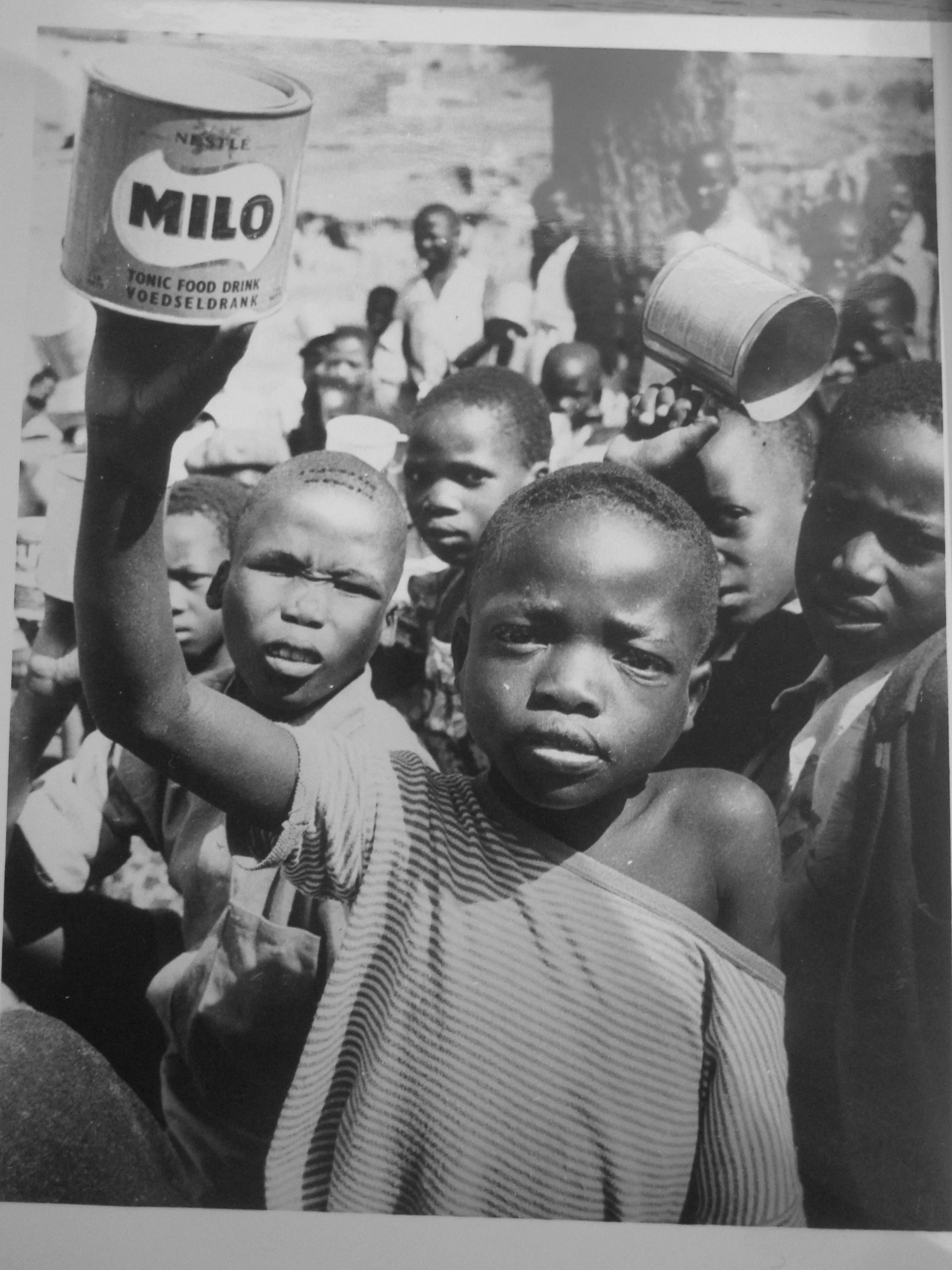

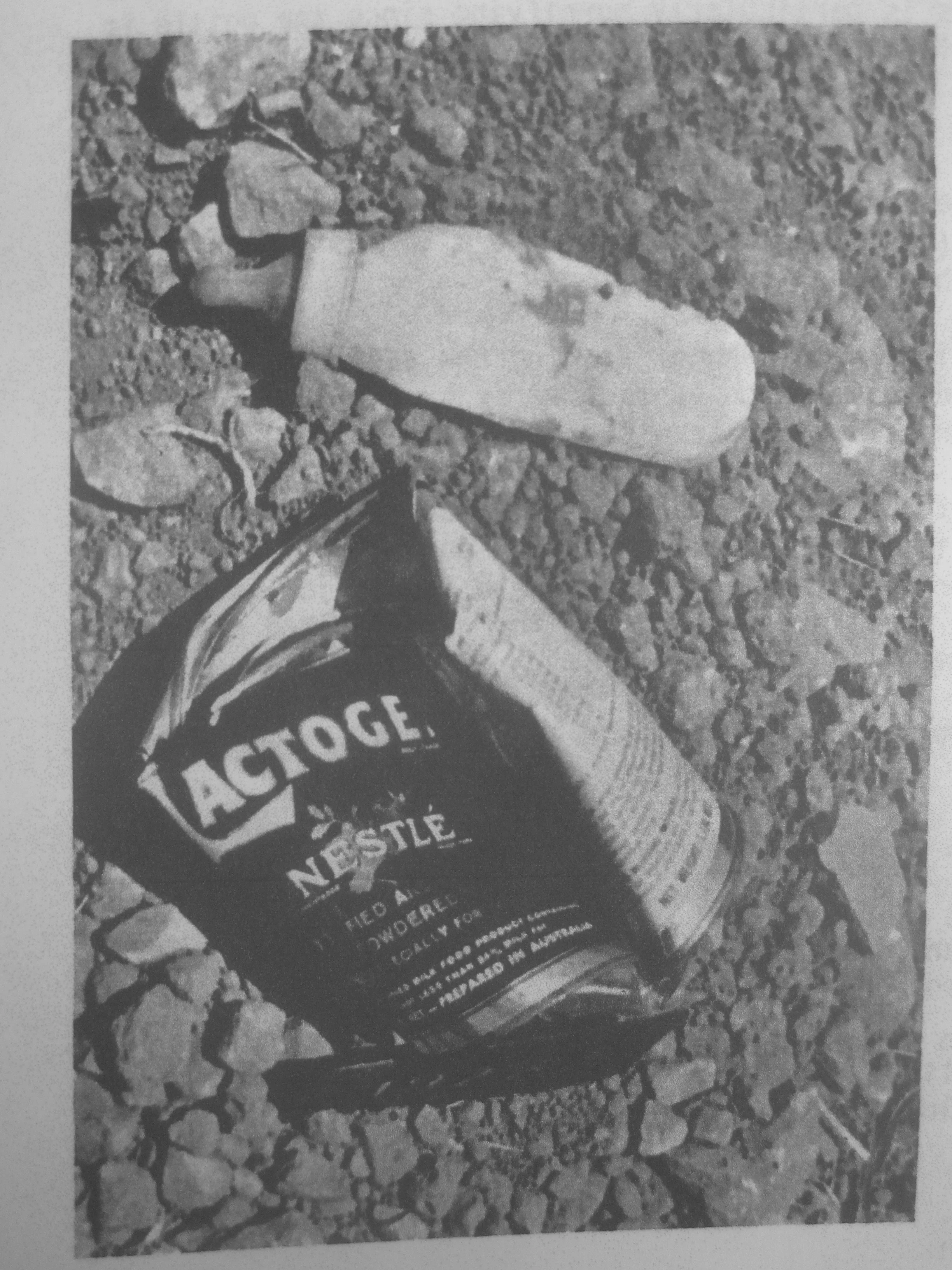

The landmark global struggles of the twentieth century—capitalism vs. communism, imperialism vs. decolonization, traditionalism vs. modernity, the West vs. the Global South, scarcity vs. abundance, the so-called welfare state vs. neo-liberalism—converged in the competing images of two babies in the 1970s. In one, there is an emaciated African infant, ribs prominent, large skull too heavy for its body, severely malnourished and near death, lying on her back next to her brother's grave. On the grave, sticking out of piled dirt, rested a baby bottle, there because of its supposed magical powers that would accompany the dead infant into the afterlife. In the other image, a healthy white baby with fat, rosy cheeks, sits next to a canister of infant formula, smiling and ready to grow and develop according to proper growth charts. Anti-formula activists distributed the first image in order to gain support for a global boycott of infant formula sold in the Global South by multinational corporations. Food and pharmaceutical companies offered the second image as an advertisement for their scientifically manufactured baby foods.

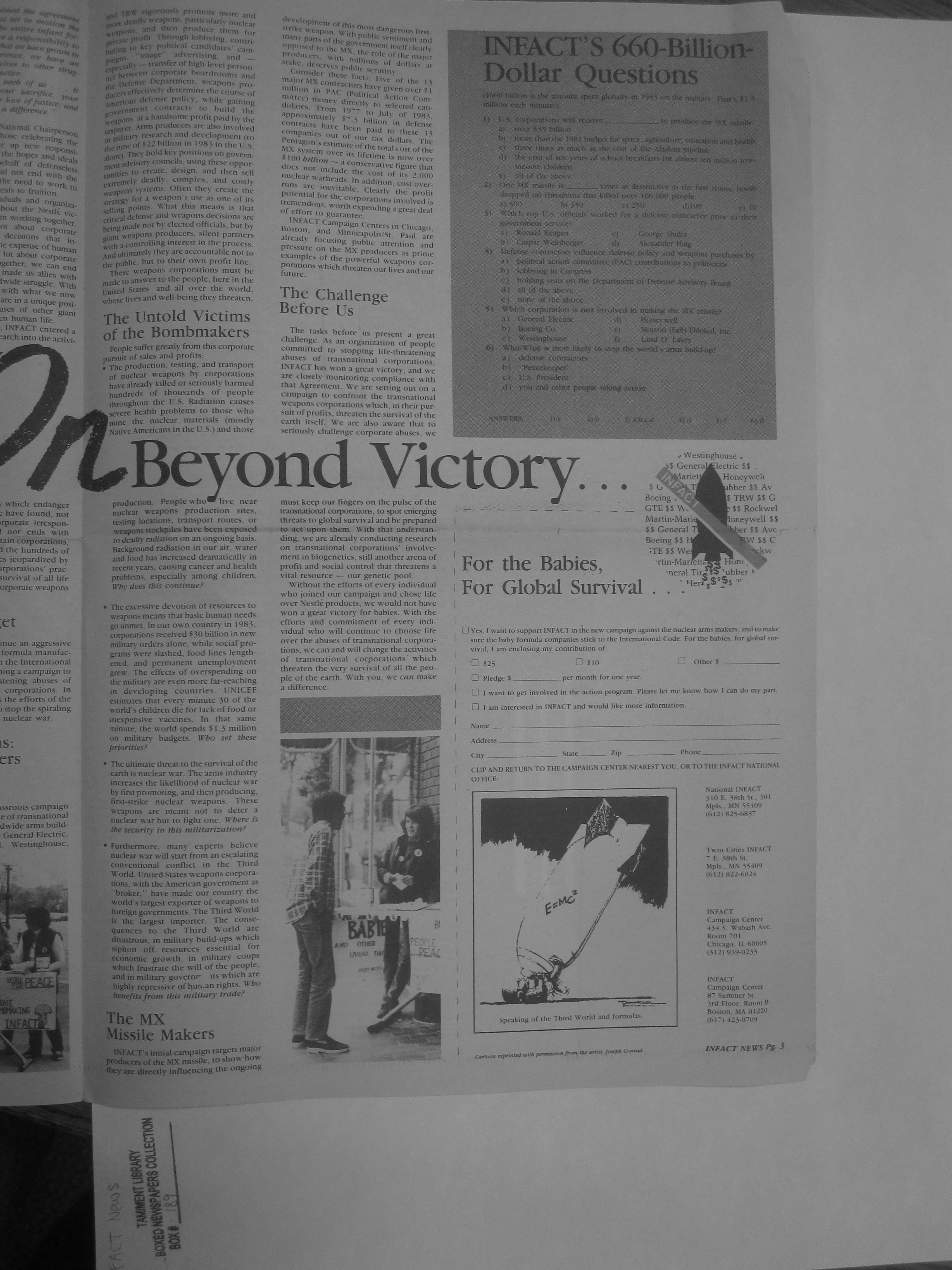

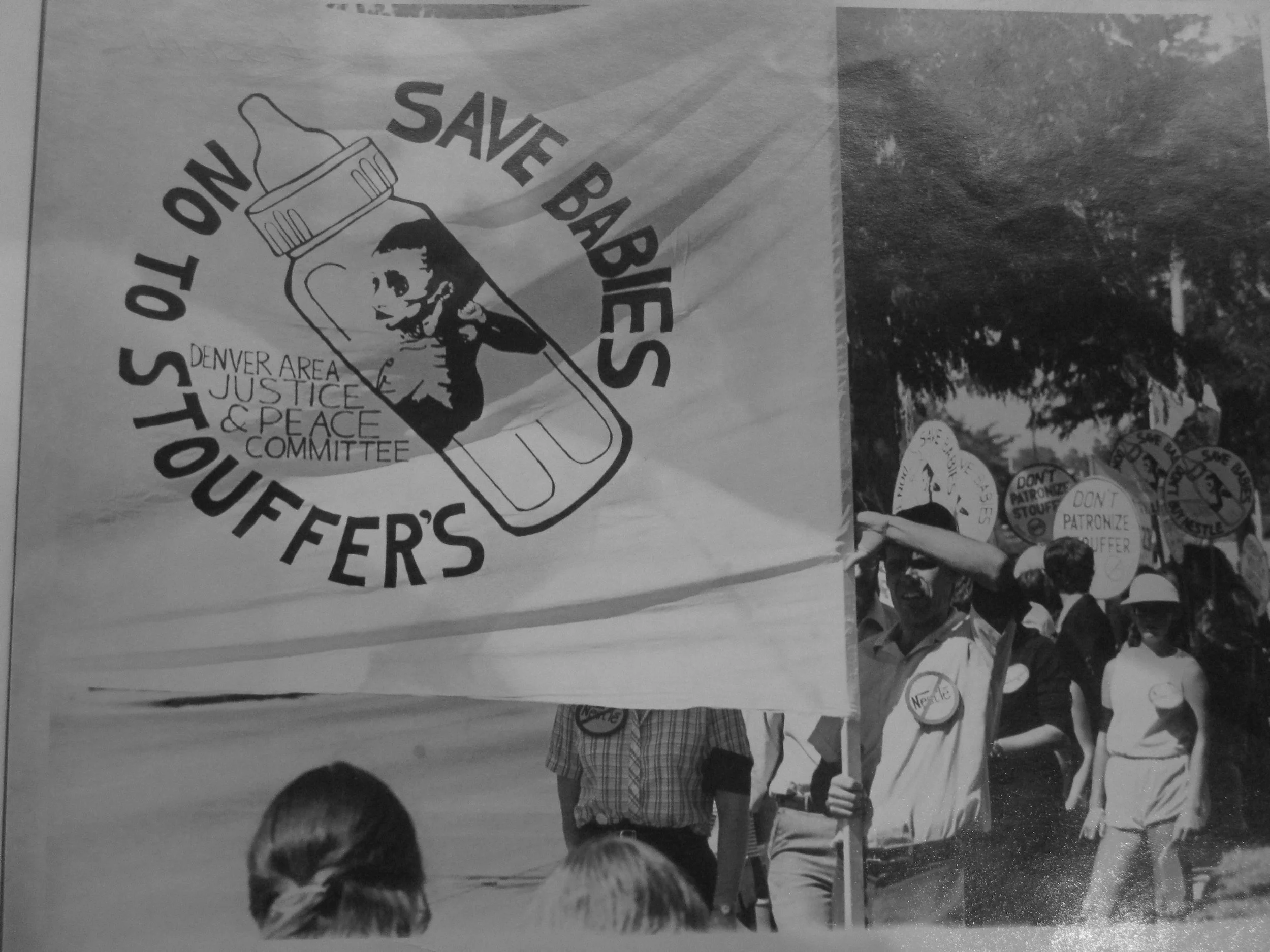

Over the last century, a range of political agendas has focused on the nursing mother and baby in order to advance, or to challenge, feminism, capitalism, humanitarianism, and environmentalism. The most crucial intervention—and the one at the heart of this project—was the commercial development of alternatives to breast milk. The very name “infant formula” suggests a techno-industrial approach to sustaining babies in ways that, depending on who was making the argument, liberated or devalued women, helped or harmed standards of living in the developing world, and promoted or impeded global environmental sustainability. The Nestlé Corporation invented powdered infant food in the late nineteenth century and immediately attracted the attention of maternalist organizations and consumer groups. The emergence of scientifically produced infant foods coincided with declining breastfeeding rates and alarming infant mortality worldwide, which created ideal conditions for a new kind of international social justice movement. Nearly a century of contest crystalized in the 1970s, in a conflict between global activists and corporate giants over the sale of infant formula in the so-called developing world.

This book narrates the international boycott of Nestlé in the 1970s and 1980s in order to investigate concepts of growth and development, ideas of universal world health, and the problems of regulating multinational corporations. Its five chapters trace the rise of baby food politics from the birth of formula manufacturing in the late nineteenth century to a World Health Organization code of conduct in the 1980s. The international politics of baby feeding involved governments, the UN, activist networks, and ordinary mothers around the world. The manuscript draws on archival sources such as congressional and UN documents, corporate records, health professional accounts and USAID research, church papers, court cases and an extensive activist archive. Its actors include NGOs, MNCs (Multinational Corporations), activists, and countless families in places like Nairobi and Bogota where Nestlé’s efforts to sell formula coincided with the long process of decolonization. Nestlé’s formula marketing was explosive for reasons having to do with domestic politics in the United States, as well as the concurrent (and often conflicting) agendas of the United States foreign policy and the developmental programs of groups like the UN and WHO.

Read More